Nero & Venus

According to the historian Tacitus, Nero was hounded to death "by messages and rumors, rather than by force of arms". The seven legions on the German frontier, the best in the empire, remained loyal until Nero threw away his crown. Had he appealed to them they would undoubtedly have stood with the descendant of Julius Caesar. The British legion remained loyal to him even after his death. In Rome the Praetorian Guards deserted only when their perfidious Praetorian commander lied that Nero had fled. He was wildly popular with the Roman plebs, he was worshipped in the East. What explains his sudden and catastrophic loss of confidence during the last six weeks of his life?

In Nero's world astrology exceeded every religion in power and influence so it is quite possible that his lethargy resulted from an astrology-inspired plot that persuaded him he was powerless to defend himself and that his only hope was to flee. The plot may have been conceived during or shortly after the spectacular appearance of Halley's comet in February 66 since comets predicted the death of kings, gathered support during the next two years and finally came to fruition in April 68. Why then? The best explanation seems to involve the movement through the zodiac of the planet Venus.

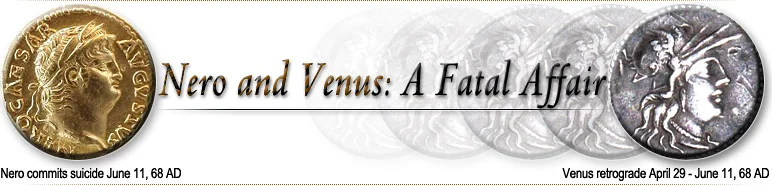

Nero had a family connection with Venus. He was the last of the Julian dynasty which claimed Venus, both goddess and star, as its ancestor by descent from the Trojan hero Aeneas, son of Venus and father of Iulus (Julius). We think of Venus as the goddess of love and lovely things but she originated as the Semitic war goddess Ishtar (Babylonia) and Astarte (Phoenicia). It was as Venus the war goddess that Nero's ancestor Julius Caesar exploited his heavenly connection. He stamped Venus in military uniform holding Winged Victory in her right hand on the reverse of his coins. His watchword for his pivotal battle against Pompey at Pharsalus was "Venus Bringer of Victory". His watchword for his final battle (against Pompey's son in Spain) was "Venus". Emblazoned on the shields of his favorite legion, the 10th, was the astrological sign Taurus. This was an unmistakable emblem of Venus because Taurus was the zodiacal throne of Venus during daylight hours. Julius Caesar built a temple dedicated to Mother Venus. Caesar's grandnephew Augustus also made the most of his family's decent from the brilliant planet.

As both Nero's ancestor and a patroness of the arts including music, it is likely that Nero drew inspiration from his family star. According to ancient astrological lore, when a planet stops its usual forward movement through the zodiac and then moves backward it loses much of its power. Venus goes retrograde more or less annually for about two months at a time. Periods where Venus went retrograde were probably thought to be unfortunate for Nero's musical endeavors because Venus was "turning her back" on him. During his reign (54-68 AD) Venus went retrograde eight times. But after his singing debut in the summer of 64 AD Venus went retrograde only twice before his death.

The first of these unfortunate retrograde events took place in the autumn of 66 AD, an import time for Nero because he was on his way to Greece for his infamous musical tour. The precise chronology of this tour is difficult to reconstruct. The records of the imperial cult make it fairly certain he departed Rome between June 19 and September 14, 66 AD. However the September date was too late in the year for a safe crossing of the Adriatic sea. Venus went retrograde between September 23 and November 3, 66 AD so the "divine voice" could not be called on for its best performance during this inauspicious time. The historian Suetonius tells us that, on his way to Greece, Nero sang on Corfu (an island off Albania)which suggests he arrived there before September 23. When he traveled to Nicopolis and then Delphi to visit the Actian and Pythian Games, these visits may have fallen into the September 23 to November 3 retrograde period when Venus could not inspire the singing emperor.

Nero was determined to conquer Greece by winning every important musical contest. These were normally held at intervals of several years, the Olympic, for example, every fourth year. Nero is mocked by hostile historians for ordering three contests to be held a second time in a single year so he could carry off more prizes. The Actian and the Pythian Games were indeed repeated a year later in about September 67 AD. But it may be that Nero didn't compete during his first (autumn 66 AD) visit to these games, which were on his way to his winter quarters in Corinth, because they were being held during the September 23 to November 3 astrologically inauspicious time.

True, he also ordered a replay of the Isthmian Games where he had originally performed in the Venus-blessed spring of 67 AD. But Nero did not necessarily hold them a second time to win more wreaths. This was the occasion when he gave Greece its freedom (November 28, 67) on the eve of his hurried and hazardous return to Italy. Since he had already won the musical first prizes in the Isthmian Games in spring, his grandiloquent freedom speech, part of which has survived, might have been his only dramatic contribution during the November 67 AD replay.

It could be that Nero chose the year 67 AD for his Greek tour because, unlike the preceding two years (65 AD and 66 AD), Venus did not go retrograde at all in 67. In the final six weeks of Nero's short life (he died at age 30) Venus shunned him again. On April 29, 68 AD she stopped in her tracks and began moving backward in the zodiac, a bad omen for a ruler who planned to vanquish his enemies with song. This was when Nero would have heard the news of his general Galba's April 3 rebellion in Spain. In an age where nothing celestial happened by chance, Venus's disdain could be why Nero, who had survived more dangerous conspiracies, lost his nerve.

At 1 p.m. on June 11, a few hours after Nero's suicide, Venus began moving forward again. No wonder Nero's enemies sent a galloping hit squad to hunt him down when they discovered he was skulking in a Roman basement waiting for fate's tide to turn. Had they allowed him to survive until then, he might have saved his famous last words, "What a great artist dies in me!" for a much later occasion.